This article will touch upon some of the most common breeding methods and practices involved in breeding pigeons, namely line-breeding, cross-breeding and inbreeding, and how each of these relates and may be used in conjunction with one another.

The aim is to give you an idea of what is involved without a heavy science lesson. That said, if you want to really delve into your own research there will be some links and references for further reading.

If you haven’t already done so, take a look at this article on choosing breeders and pairing suggestions before continuing here.

Contents

Line-Breeding

Line-breeding in pigeon racing as it’s talked about and practised today is actually a form of inbreeding (to a certain degree) and as such is often mistaken as being one in the same thing, this is understandable.

Otherwise known as the cornerstone of selective breeding, line-breeding in racing pigeons essentially involves breeding around usually a single pigeon, but sometimes an original pair, in an effort to cultivate and increase the potential of reproducing the favourable traits associated with the original genetics you are line-breeding around.

Additionally, by line-breeding as opposed to cross-breeding (more on that later) we are seeking to maintain the qualities of the original bird rather than diluting it down, or (crucially) adding to it.

Len Vanderline mentions the following in an article,

“In its true form a breeding line can be traced back to a single champion bird, whereas most so called line-bred pigeons are bred around a number of related birds and by the very definition these are in-bred birds”.

Line-breeding Vs Inbreeding

We can not refute the above statement so in order to alleviate any confusion met when defining what line-breeding of pigeons really entails and how it relates to inbreeding.

Instead of trying to point out what makes inbreeding different from line-breeding, it is much simpler to accept line-breeding as a form of inbreeding, with the difference being to what extent or degree a bird is inbred.

For example, father to daughter or mother to son, we may consider being ‘extreme inbreeding’ while pairing half brother to half sister, on the other hand, is a lesser form of inbreeding and will most likely take place as we seek to maintain our chosen bloodline through our line-breeding process.

Example of Line-breeding

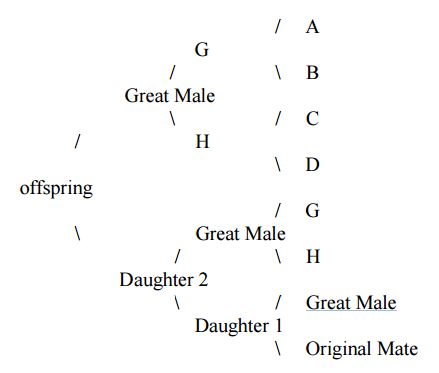

Below is an example of line-breeding through 3 generations of pairing an original Male to his best daughter (extremely inbred).

Cross-breeding (out-crossing)

Cross-breeding or out-crossing, as it’s sometimes known, is basically when we mate pigeons of a different strain, usually with no common ancestors in the previous 5 generations.

We may be looking to introduce new genes into the pool or simply want to breed more dynamic birds with increased vitality.

“A crossing of two different bloodlines tends to result in more dynamic youngsters with increased vitality.” – Gallez Jules

That said, at the same time we must be sure that the genes we introduce have the best chance possible of improving the existing gene pool rather than hindering or diluting it. For this reason, again, proper loft management and recording keeping must be emphasized.

When introducing new blood you might think of the initial round of youngsters as prototypes that need to be “stress” tested before you really accept the new pair of breeders into your stock loft or long-term strategy.

Let’s say you breed 3 or 4 youngsters from the same crossed pair, now look at them as a collective unit, how these birds do as a whole will tell you a lot about the ‘overall’ effectiveness of a breeding pair. The testing might take place during training or young bird racing.

You have to ask yourself if getting 1 decent pigeon out of 4 is really that positive an outcome for the ‘test pair’, especially if the cock bird you’re breeding from has great breeding himself with results in his own right and a clear family history of successful ancestors.

Some fanciers like to “split test” the same cock with multiple hens simultaneously. This is a very quick way to test out multiple pairings (and hens) but you run the risk of spreading yourself (and the cock bird) thin, and perhaps only allowing him to produce 1 or 2 youngsters with a specific hen may not yield enough data to properly test that pair’s compatibility.

An interesting point to make here is the combination of both of the above strategies by first casting a wide net, i.e. split testing the same cock with multiple hens to yield a few prototypes and then testing these out.

Providing you see some clear potentials you then proceed to breed quite a few more from that same cock and hen combination and do a second round of testing being sure to look at the group as a whole as well as each bird individually in your considerations moving forward.

Inbreeding

As stated previously, inbred pigeons tend to have poor vitality and are more prone to sickness.

John Halstead mentions that he tries to keep a line-breeding theme in his breeding and goes on to state he rarely inbreeds pigeons too closely, though “half brother and half sister may be considered”.

While the issues of vitality and sickness are clear, what is also apparent though is that when used correctly, inbreeding seems almost central to the success of many champion fanciers, playing an underlying role in many breeding plans and strategies.

So far we’ve covered how inbreeding relates to line-breeding and determined that it is indeed a tool for success providing it is used correctly and controlled. Now we will consider how pure or extreme inbreeding itself might be used as part of a potential long-game strategy.

Super Breeders

There are cases in which very close inbreeding is used to create pigeons bred with specific genes solely for stock. It’s almost as if the later generations are being primed or engineered to be ‘Super Breeders’ ahead of time.

Let’s examine this idea a bit closer using a very simple chart showing inbreeding within just one generation followed by an example real-life case.

In the chart below we can see that inbreeding between the ‘original cock bird’ and his best daughter yields us with reliable carriers of the original cock’s genes albeit low vitality birds. As such these pigeons are not to be raced nor judged on any kind of performance.

We then cross-breed those with birds from a completely different strain to produce dynamic youngsters with good vitality and a very good probability of carrying the desirable genetics from our original cock.

The concept shown above is a much simpler breakdown inspired by an interesting piece written by Steven van Breemen.

In his article Steven explains how he created ‘super breeders’ originating from a pigeon called Old Klaren from De Smet-Matthijs.

Steven did this through numerous generations (over a period of 25 years!) in which he paired the grandchildren of Old Klaren with each other. He then paired these grandchildren with his next generation of direct Klaren inbreds creating his so-called ‘Super Breeders’. He went on to cross these pigeons with other strains, he mentions Janssen’s as being the best combination for him though he tested numerous pairings.

Summary

Here’s a short clip from John Halsteads ‘Breeding, Feeding, and Tactics to Win Races’. John talks about the different breeding methods he puts into practice in his own loft and the various pros and cons of each.

We’ve covered quite a lot in this article, hopefully it’s given you some more ideas and strategies to implement in your own breeding plans.

In truth we’ve only just scratched the surface here, if you want to learn in more detail you might take a look at a few of the references linked in this article. If you really want to go deep into the genetics side of things we highly suggest taking a look at this website as a potential starting point.

It takes a lot of time, study, testing, planning and perhaps above all patience to do really well in this sport. A successful loft that produces consistent results is built up over many many years.